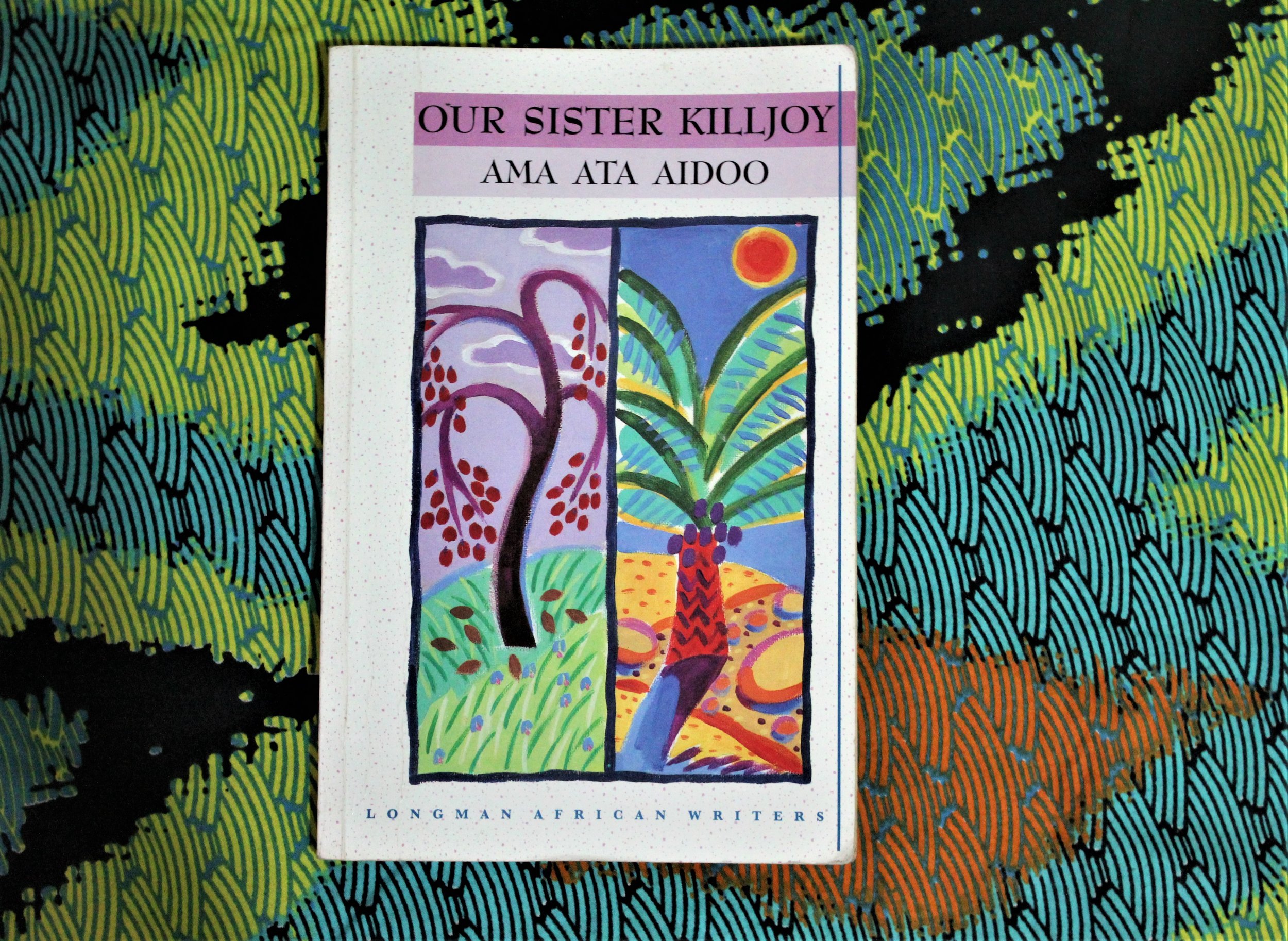

Our Sister Killjoy|Ama Ata Aidoo

Photo: Shayera Dark

Ghanaian author Ama Ata Aidoo’s debut novel Our Sister Killjoy: or Reflections from a Black-eyed Squint is an exploration of Africa’s problems with relation to Western interference and testifies to the predicament in which the continent finds itself today. Published in 1977, and written in prose-poetry, the story is told from the point of view of Sissie, the Ghanaian woman who is accepted on an academic programme in Germany to work in a pine nursery. Through personal observations and conversations, she delivers a sarcastic and humorous discourse on a myriad of issues ranging from the borrowed Victorian idea of billing strong, outspoken women as unladylike to white saviour-ism.

On her arrival to Frankfurt, Sissie is compelled to acknowledge race for the first time after a German girl calls her a “black girl”. Confused, she turns around to find everyone around her is white, and though she considers the presence or lack of melanin inconsequential, she concedes that such differences constituted the basis for apartheid in South Africa, the transatlantic slave trade and colonialism.

“…For this is all anything is about. Power to decide who is to live, who is to die,” she reasons.

When a German acquaintance asks Sissie her name, she tells her she can call her by her Christian name Mary—a ladylike name suited for school and the office (foreign concepts)—thus illustrating the expurgation of African identity by Western missionaries. Historical accounts abounds with Africans being barred from mission schools until they dropped Gitonga, Chinedu and Efua for George, Caty and Elizabeth. Case in point, before Mandela was Nelson, he was Rolihlahla until his white teacher decided otherwise. For her part, Sissie mockingly explains that Mary pleases the White God’s and his angels, who “take roll-calls in Latin” and would rather not twist “their delicate tongues around names like Gyaemehara.”

To be sure, Sissie doesn’t let Africans get off lightly for debasing the continent either. She censures “Champagne sipping ministers and commissioners sign[ing] away mineral and timber concessions” as well as corrupt African presidents—some of whom prefer governing from Europe— for perpetuating the destruction wrought by colonialism.

The book’s final chapter, written as a love letter, addresses brain drain, another pertinent African issue. A frustrated Sissie takes on poor Africans in Europe who mask the reality of their miserable working lives from their family back home, making them believe they can cater to their incessant requests. Her animus, however, is reserved for government sponsored graduates who prefer to rail against the problems of Africa but refuse to return to fix them. Most offer her flimsy excuses for their self-exile, with the exception of her lover, a medical researcher. He voices the concerns of many educated Africans in the diaspora: the lack of a conducive working environment.

“...to equip a first-class research set-up for me would swallow the annual budget of the Ministry of Health,” he says. Although Sissie grudgingly concedes his point, she tries but fails to make him buy her idea of a brighter Africa.

Our Sister Killjoy is a searing analysis of the unhealthy and unequal relationship between Africa and the West. Each page rattles the chains that continue to hold Africa back from greatness, exposing the tyranny of its greedy, visionless leaders and the parasitism of self-serving foreign powers.

You May Also Like